I was following a story when I chose Islas de Gigantes and Sicogon Island as this trip’s destinations. I knew about the Ayala development at Sicogon’s Barangay Buaya and I wanted to see the island as it was before high-end resorts, manicured beachfronts and jetskis take over. I also knew that Gigantes was its neighbor. Any development in Sicogon was bound to seep into this chain of islands. That’s how cancer works… err, tourism, I mean.

Too heavy too early? Sorry 🙂 Let me backtrack by saying that I also came to eat. As in, if you love scallops, and huge crabs and squid, you should take the next plane to Ilo-Ilo! Stay at Gigantes Hideaway, run by former Carles tourism officer Joel Decano; and your tummy and hunger for adventure would be well cared for.

Hideaway was the best – well, hideaway in Gigantes Norte, the north side of the group of islands. No mobile signal, simple accommodations and very generous with their seafood, the place was perfect. It also meant an audience with Joel, a controversial local figure and the man who first explored the Gigantes sites for tourism.

The Route

My trip to these islands was easy. From Manila, I flew to Roxas City; from where I got on a flying FX van for Bancal, Carles. (It normally took more than two hours to get to the Bancal jump-off. Somehow, I managed to get there in a little more than an hour. Lumipad ang FX!)

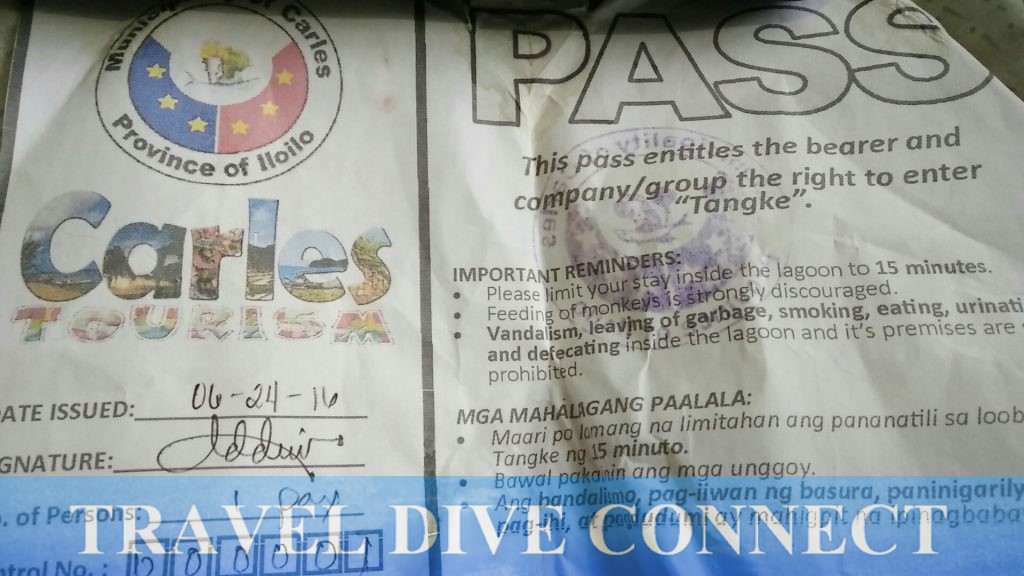

There was a Carles tourism hut at the Bancal port. The people who welcomed me were friendly and solicitous. They put together what I needed: a boat ticket for Gigantes and a permit to visit Tangke, a hidden lagoon that was the highlight of any Gigantes island-hopping trip. (I didn’t even know I needed a Tangke permit.) I didn’t think it was a big deal.

Apparently, this was an uncommon route. Many would opt to use the port of Estancia, which was an hour further from Bancal. It offered an afternoon boat ride to the islands, and a bustling wet market for supplies. The municipality also had banks and ATM machines. Of course, being outside the jurisdiction of Carles, no one from the tourism office was around to meet travelers.

Again, to an outsider, this did not seem like a big deal. Route options were typical, especially for places like Gigantes, which only had one boat per day to/from connecting ports.

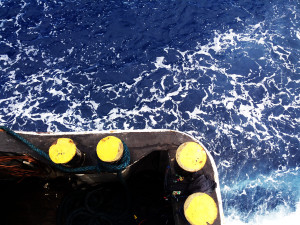

On the Bancal boat, I met a few local DENR employees. They were taking their Mindanao counterpart around. I mixed in with them when the counterpart, a nice older woman, “ordered” my solo-traveling mug included in their groufie. Introductions followed; and I was able to talk to them about Gigantes and Sicogon. That was a lucky encounter.

A Gigantes Welcome

We parted along a nondescript Islas de Gigantes beach where our boat docked. There was no marker or anything that indicated the place as the port, except for a handful of people waiting and around 5 motorbikes. And definitely, there was no tourist facility similar to the one at Bancal port.

The group of islands retained its rustic feel, despite the steady flow of tourists. Aside from not having the requisite traveler facilities, their roads were largely unpaved and big enough only for two motorbikes. There were no big houses nor concrete edifices to give it a more touristy vibe. I stayed in a small nipa hut big enough only for a single bed and a small bathroom. (It was their best hut, and I had a porch with a papag and a hammock. It was awesome and I hung out here a lot.)

There was also zero mobile and internet signal in almost all of Gigantes. For the few times I really needed to go online, I had to take a 30-minute hike to the “call center,” the barangay’s highest point. An enterprising family had taken advantage of the location, and expanded their sari-sari store to include a couple of bamboo benches.

To get anywhere, you either walked or hired motorbikes. Life was slow and simple. And, I didn’t really mind. I found the disconnection liberating.

The Birth of A Giant

My host, Joel, had a lot to say about the development of local tourism in Gigantes Island. He’d been on both sides. A former OFW, he found it hard to re-enter the fishing industry in his home province. This moved him to explore the tourism possibilities of Gigantes. His success led to the thriving Hideaway Inn; and later, a government assignment under the municipal tourism office.

“There was an obvious decline,” Joel said. “I remember Gigantes as having seas so abundant that fish would literally jump into the nets of our fishermen.” Now infested by commercial fishing boats, their harvests dwindled and fish got smaller.

The quality of Gigantes’ seascape also declined. Some coastlines were now trashed with strewn scallop shells. Picturesque limestone cliffs, islets and sandbars sat on bare ocean floors that, I imagined, were once teeming with corals and fish.

The DENR rep I met on the boat took only a little prodding before she confessed the island’s shameful past – that, in spite of its seeming abundance, its fishermen resorted to illegal fishing practices in order to keep up with their commercial counterparts. These practices had been put under control, according to her, “but there is still a need to organize the locals, especially those who work as guides.”

Indeed, the island had turned to tourism to make up for their dwindling fish catch. Joel started with a few select guests. He prepared tour packages that included Gigantes’ highlights; and picked up guests, usually foreigners, passing through Boracay. His home was the first Hideaway.

This was noticed by the municipal government, and an alternative industry began.

Once On This Island

My experience ran counter to some of the DENR rep’s claims, particularly that one about getting the locals organized. There seemed to be an established system among the local tourism stakeholders – or, at least those who worked with Joel, the former Carles Tourism Office head.

The same packages that helped initially bring travelers to the island were still in place. I needed to stay a few extra days to hang out with Joel and do a few things outside the typical itinerary.

But, it’s all good. Even for solo travelers like myself, the options at Gigantes were varied and affordable. Set charges were implemented for everything – you won’t need to haggle or worry about overpricing. Guides worked like your personal concierges, arranging and practically doing everything for their assigned guests. They coordinated my day trips with their barangay-based peers, motorbike drivers and boatmen. They scheduled and served my meals, and even bought beer for me. Up until I boarded the boat for Estancia, where I caught another boat for Sicogon, my guide was on call to make sure I was comfortable. It felt safe. And, except for a Tangke incident I partly witnessed, it felt orderly.

Highlight: Tangke Hidden Lagoon

Gigantes Island is made up of Gigantes Norte and Gigantes Sur, and a few clusters of smaller islands. Most of the inns and resorts were located at the Norte island. Norte had the port, Bakwitan cave and the old lighthouse, recently restored by the ABS CBN Foundation. (If you love adventure and a little challenge, don’t miss Bakwitan cave. Of course, make sure you’re fit enough for some hardcore spelunking first. Why hardcore? Kasi wala kang harness.)

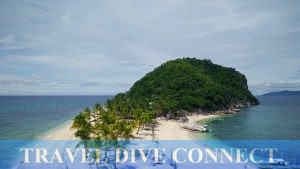

You got a feel of Gigantes Sur when you go island-hopping. Must-see islands included the picturesque Cabugao Island and Antonia’s Beach. And, Tangke Hidden Lagoon, for many, was the highlight of a Gigantes island-hopping trip. It was something you’d imagine only existed in movies.

Just think of the bluest waters – chest or chin-level safe, depending on the tide – and surround it with the browns, grays and greens of limestone cliffs; and the blues and whites of sunny skies and the vast ocean. A stunning lagoon in the middle of nowhere.

Your approach would not reveal this sea lover’s prize right away. You anchored along volcanic boulders. Take a few steps inward, onto boulders and rocks, careful not to slip; and you’d be rewarded with the breathtaking sight.

Visitors only had 15 minutes to enjoy Tangke. This was enough time for a few pictures, the mandatory selfie (which I did not do), and a short swim. If one dared, you could do a 20-feet cliff jump close to where boats docked.

The 15-minute limitation came with the lagoon’s increased popularity, and was just recently implemented. Along with this, a permit to visit was now required. The idea was to control tourist traffic so that Tangke could remain pristine. However, as noble as this was, it seemed to have forgotten important components in any conservationist action: the tourist experience and the local tourism stakeholders.

The Tangke Incident

You could only get the permit at Bancal, practically requiring travelers to pass through the young port, one that lacked amenities such as completely paved roads. The requirement was also loosely implemented.

In the past – as in just a couple of weeks before my visit – the actual paper copy of the permit was not strictly required. As long as visitors paid the environmental fee through their inns, they could visit the lagoon. When I was there, however, an incident with Manila-based lawyers highlighted the flaws in implementation. (The lawyer part stuck with me because they vowed to sue the local government.)

This group stayed at Hideaway so they also had their concierge/guide to take care of booking their island-hopping trip. All was in place, and Tangke was their last destination. Before this, they docked at Bantique Island Sandbar, an idyllic strip of sand that’s perfect for relaxing and tampisaw. Here, they were approached by a tourism staff member (he wore the official vest). He said that they weren’t on the list of guests; and that they needed to pay twice the fee amount because they didn’t get the permit from Bancal. They obliged; they wanted to see Tangke.

Receipt in hand, they sailed for the lagoon. Tourism officers there however turned them away. They wanted the actual permit. Frustrated, they went back to the sandbar to confront the staff, and at least get their money back. This too was denied.

At The Foot of The Sleeping Sicogon Giant

This could just have been an isolated incident, the unfortunate repercussion of having tourism personnel who lacked training. But, then again, how many turned-away travelers would it take before the municipality actually considered what it took to get to the island chain and our limited route options? When would they involve Carles stakeholders – those who actually lived in Gigantes and interacted with its tourists – not just as foot soldier, but also as policy planners and implementors?

Joel asserted that there was a disconnect between the municipal government and the people of Islas de Gigantes. This showed in policies and government services (or lack of) that didn’t really reflect the needs of the locals. According to the former Tourism official, there had been several incidents in which their welfare was strewn aside for the sake of bureaucracy. Joel mentioned the ABS CBN/ Gina Lopez (now the current DENR chief) brouhaha wherein the private organization’s donation to Decano and the locals was questioned. This resulted in the project’s cancellation, leaving them with little tourism assistance.

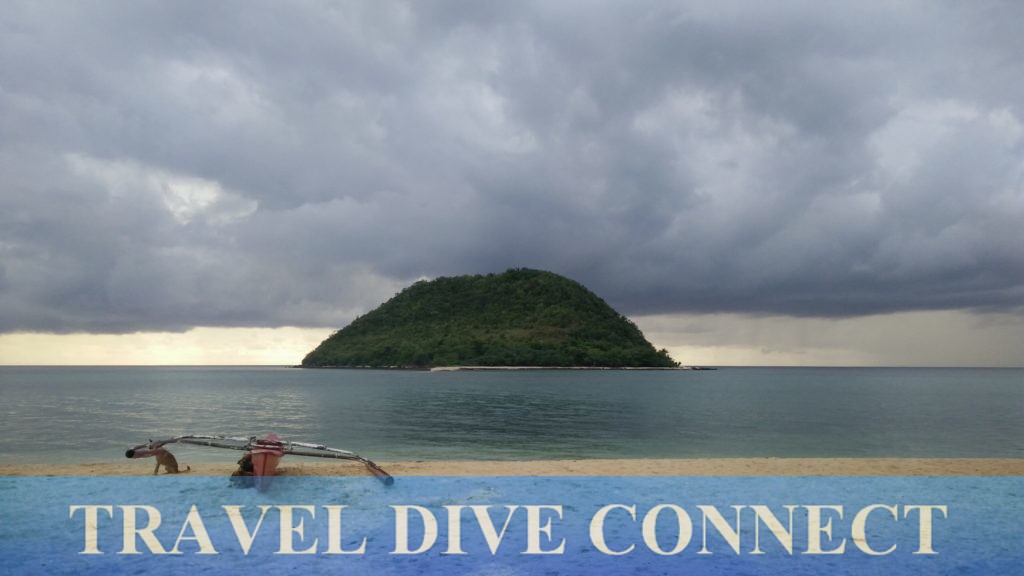

Now, there was the Tangke incident. If anything, all this was indicative of an ill-prepared Carles in the face of a coming tourism boom. An industry giant was at the helm of Sicogon’s awakening. Nothing would stop the tourist surge.

“At the very least, they should get someone from Gigantes who could be a voice, a representative of the island,” Joel said. “We are already organized. We just have to regroup, and get more involved in tourism policies. After all, we – our people and our natural resources – are the ones directly affected.”

The sleeping Sicogon giant would awaken soon. It’s time for the municipal government of Carles to act.

Source:

Joel Decano of Gigantes Hideaway Inn

Asluman, Gigantes Norte,

Islas de Gigantes, Ilo-Ilo

Should you have more questions or are interested in booking, please send him an FB message or PM me for contact info.

Tacloban was not the destination during my last trip but I needed to pass through the city. I dreaded to pass through it. It was my first time but it felt otherwise. Popular media had already mapped a Tacloban that suffered tragedies both natural and unnatural. The city, post

Tacloban was not the destination during my last trip but I needed to pass through the city. I dreaded to pass through it. It was my first time but it felt otherwise. Popular media had already mapped a Tacloban that suffered tragedies both natural and unnatural. The city, post

So, on the way back from Padre Burgos, I decided to spend the time before my flight exploring

So, on the way back from Padre Burgos, I decided to spend the time before my flight exploring