For my mid-summer trip, I went to Mindoro – to both its Oriental and Occidental sides. It was a logistical decision. I had three trips lined up for the next few months. I chose to do this first because I was unsure of the political situation in Lubang Island, Occidental Mindoro, my main point of interest.

It was best to visit before May 2016’s election as their mayor of three terms could not run again. Lubang’s planned ecotourism development was one of Mayor Col. Juan Sanchez’ (Ret.) initiatives.

Sabang, Puerto Galera, Oriental Mindoro was added to the mix because I wanted to dive along the Verde Island Passage, referred to by marine conservationists as the “center of the center of marine shorefish biodiversity.” The passage separated Luzon and Mindoro, and it was one of the busiest naval thoroughfares in the country. Some of the best spots to dive were sites near Verde Island, which was only 40 minutes away by boat from the Galera tourist hubs.

Sabang, Puerto Galera, Oriental Mindoro was added to the mix because I wanted to dive along the Verde Island Passage, referred to by marine conservationists as the “center of the center of marine shorefish biodiversity.” The passage separated Luzon and Mindoro, and it was one of the busiest naval thoroughfares in the country. Some of the best spots to dive were sites near Verde Island, which was only 40 minutes away by boat from the Galera tourist hubs.

This was a surprisingly long trip for me. Being side by side on the map was deceiving. There were a lot of transfers. Nasugbu bus – Wawa tricycle – Tilik, Lubang boat from Wawa Pier – back – tricycle again – van for Batangas port – boat to Sabang and back – bus to Manila… kapuy!

But it was worth it. 🙂

Occidental Paradise

Lubang Island, Occidental Mindoro kept its promise. My days there were filled with beautiful beaches, mountain treks to historic caves and cool waterfalls, and Tiya Amen’s amazing cooking. The Onoda Trail, Hulagaan Falls and Kibrada Turtle Sanctuary were notable destinations.

Onoda Trail

Lubang was best known for being the home of the last Japanese straggler, Hiro Onoda. Onoda was an intelligence officer of the Imperial Japanese Army who went into hiding after World War II. He stayed in a series of caves along the hillsides of Lubang and Looc, and survived on wild chickens and fruits.

The trail to these caves had been cleaned up and installed with natural footpaths and handrails made out of tree branches. Three of the first four caves were open for half-day trips. It took two hours to reach these caves, at an average climbing pace. Highlights for me were the musical wall of Cave 4, and the impressively pristine condition of the caves.

I’d visited popular caves in the past, notably Sumaging in Sagada and Callao Cave in Cagayan Province. These natural wonders, while still majestic, had obvious traces of human traffic, such as erosion and vandalism.

The Onoda Trail caves, despite the marked path that led to them, remained rough and natural. At some point, I was actually scared of going further inside these caves, afraid I’d encounter snakes. (There were none; although, I did duck when a couple of frightened bats flew out.)

Hulagaan Falls and Kibrada Turtle Sanctuary

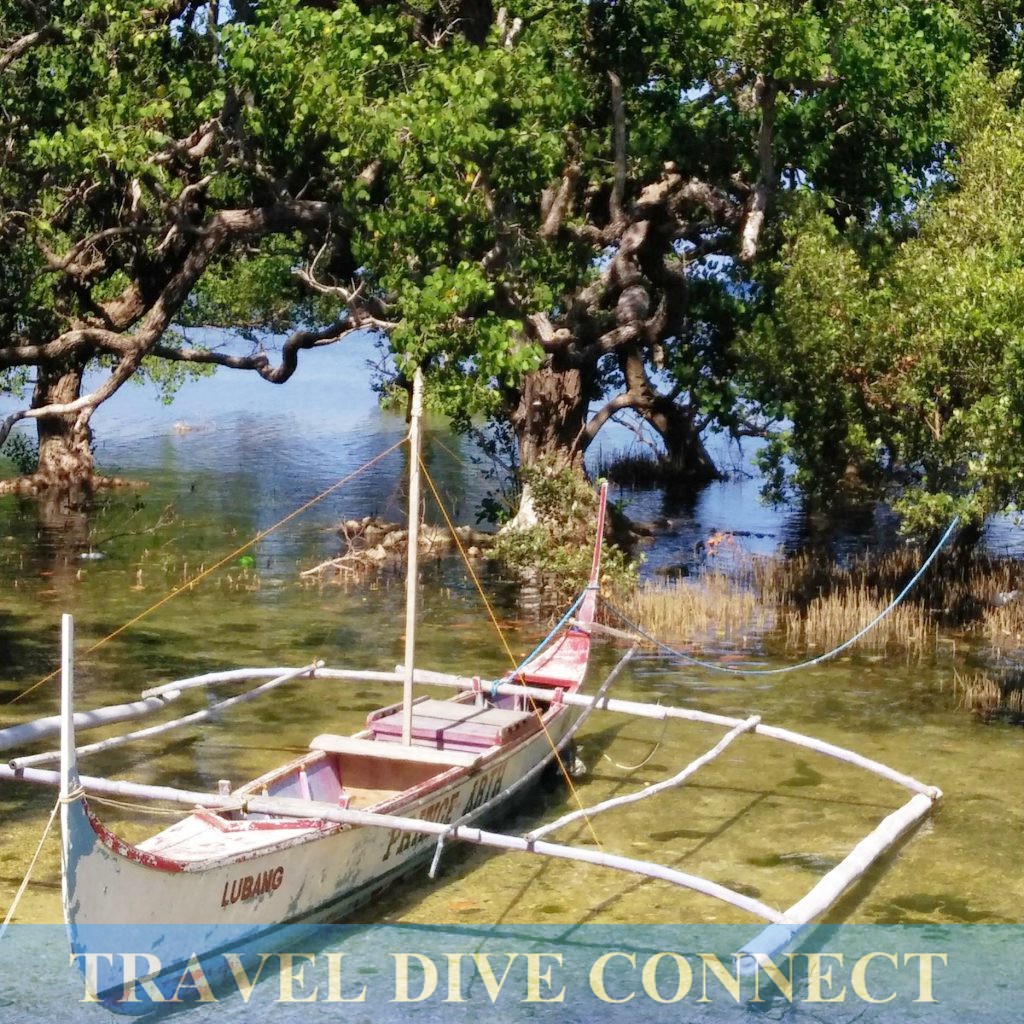

Hulagaan Falls via Hulagaan Beach, and Kibrada Beach were located relatively close to each other. However, Kibrada faced the open sea and access depended on the waves. Too strong and it would be dangerous for our small boat to make the crossing. Lucky, the ocean was calm that day.

Including a stopover at the RSM Coral Farm in barangay Tumito Sawang, this trip took a whole day. We headed to the turtle sanctuary first to make the most of the sea’s calmness.

From our jump-off point at Binakas Beach, Kibrada Turtle Sanctuary was 40 minutes away by boat through some of the most spectacular seaside formations I’d seen so far. Limestone cliffs, volcanic rocks jutting out from the sea, and strips of empty white sand beaches – I could’ve just stayed on the boat and I’d be happy.

Kibrada was home to nesting turtles. During season, as many as 20 turtles a night would come up to lay their eggs. There were a few cases of poaching, mostly by outsiders according to my guide. The municipality assigned guards when they expected a lot of turtles.

Yes, Kibrada belonged to the pawikan – I was the guest. As we walked the empty stretch of beach, my guide would point out turtle tracks, some of which were a couple of months old. Overnight campers were allowed on the beach in limited numbers, and only when accompanied by a municipal office-assigned guide.

Close to lunch time, we made our way to Hulagaan Beach. This was a small cove that had a few amenities for – well – us humans 🙂 There was running water, a roofed structure for meals and naps, and his/hers bathrooms. Overnight campers were also welcome, again as long as they got permission and guide services from the municipality.

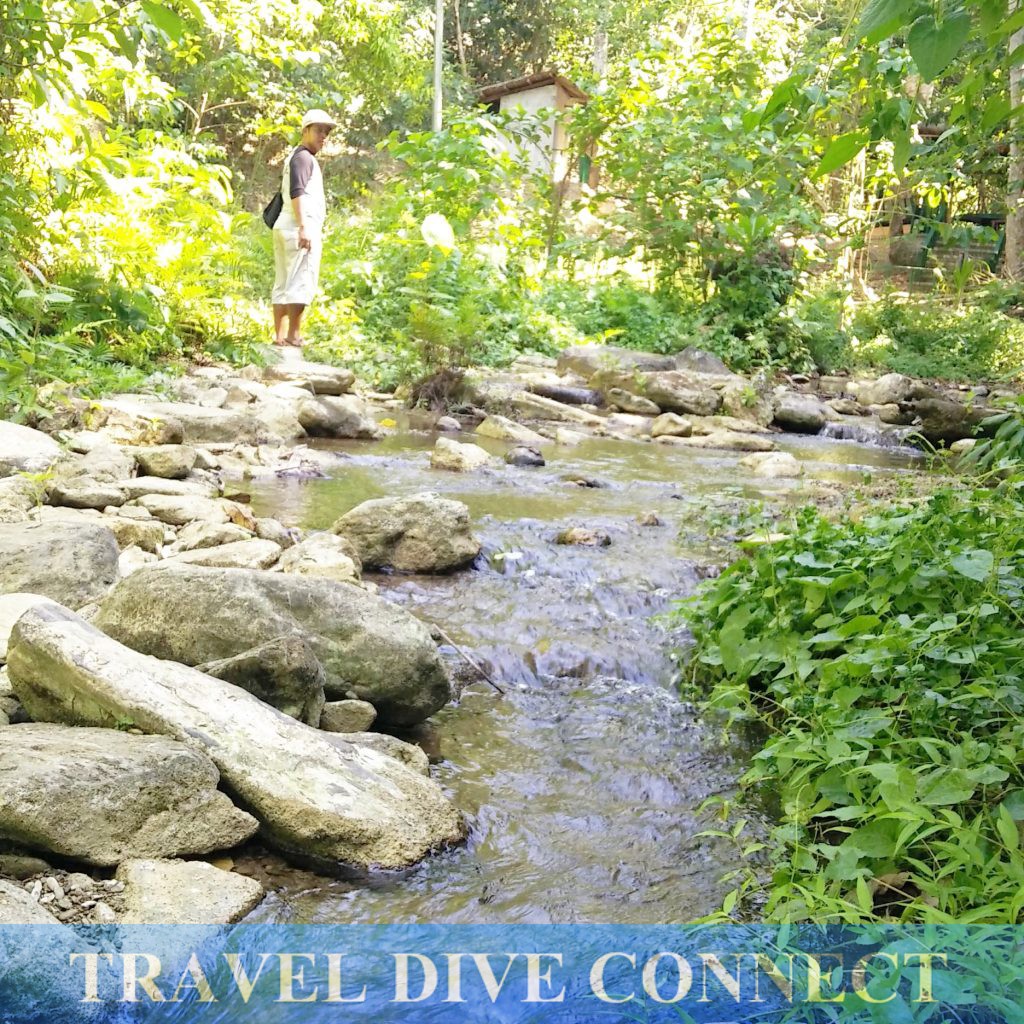

I wasn’t hungry yet so I suggested that we go to the falls first. This was a 15- to 30-minute trek, mostly through boulders and streams. You got wet along the way so wet-clothes, no-slip sandals and waterproofed gadgets were requisite. Like at the Onoda Trail, there was a cleared path to the falls. Ropes and handrails fashioned from tree branches were installed where necessary.

Hulagaan Falls was a small crevice etched in the middle of an arena of volcanic boulders and trees. Cool water gushed from it, down into a small pool where freshwater fish played. You knew that humans frequented this place. The fish weren’t afraid of me. Some of them even took nips. I stayed there for a bit, thankful for the break from the heat.

Our last stop was at the RVS 4 Star Coral Farm. A collaboration between private individuals and the Lubang municipal government, the farm cultivated maricultured corals for replanting in Lubang waters and elsewhere if necessary. The beach of Tumito Sawang was not as pretty as the rest; and snorklers who wanted to see the underwater installations had to go through colonies of sea urchins. There was also a bit of current at around 2PM. But it was an interesting visit – a first for me, actually – my first time to see an operational coral farm.

Tiya Amen’s Homestay and Catering

There was a range of accommodations to choose from when visiting Lubang. From beach-side resorts to homestay houses, you had options that fit your budget.

Cabra Hotel, facing Cabra Island, was something to watch out for. They planned on catering to the diving community but was fairly new in the business. They still had to hire qualified dive center staff.

Homestays were popular, and Tiya Amen’s place was on most everyone’s wish list. Heck, when I was there, I would meet residents of nearby homestays almost daily. The food at Tiya Amen’s was the best!

Tiya Amen was just a year shy of becoming an octogenarian. But, don’t let the number fool you. She’s as strong as an ox. She woke up at 3AM every day, even after nights when she slept later than I did; jogged at least 3 laps around the block every day; and ran her catering and homestay businesses.

For one daily fee, I got my own room, and access to wi-fi, television and the lounge area, as well as distilled water and three meals a day. She also prepared merienda but I usually hid at this time. (Busog na busog kasi!) There was always a lot food. I feasted on crabs, shrimps and lobsters – all fresh daily catches bought from her early morning trip to the wet market.

Lubang Impressions

Lubang Island became one of my target destinations because I was impressed by their tourism officer when I met her at an ecotourism seminar. Her municipality had adopted the Tourism Master Plan put together by Blue Water Consultancy, which had sustainability, conservation and people-centric development at its core.

They began to implement the plan around the start of the decade; and had since been the recipient of praise, awards and such. 2016 was all about an election that may change the direction of their tourism initiatives. It was also about the culmination of their Master Plan. With only a few roads and an airport to complete, by the end of the year, they expected to finally be ready for “tourism” – the best and worst that this term had come to mean.

So far, “un-ready” Lubang was the island of my dreams. It was peaceful and virtually crime-free. I woke up to pots and pans, and titas’ and lolas’ kitchen chatter in the morning. Road trips – not just boat trips and hikes – offered skies where egrets, crows, yellow-chested birds (Yellow breasted bunting? I really don’t know.) and owls flew freely. I trekked up mountains that were clean and felt safe. I swam in clear freshwater lakes and seas. I had white-sand beaches to myself.

So far, “un-ready” Lubang was the island of my dreams. It was peaceful and virtually crime-free. I woke up to pots and pans, and titas’ and lolas’ kitchen chatter in the morning. Road trips – not just boat trips and hikes – offered skies where egrets, crows, yellow-chested birds (Yellow breasted bunting? I really don’t know.) and owls flew freely. I trekked up mountains that were clean and felt safe. I swam in clear freshwater lakes and seas. I had white-sand beaches to myself.

This quality was, to an extent, shared by other Occidental Mindoro locations I’d visited. San Jose, Calintaan, Sablayan, and Sablayan’s Apo Reef retained their seeming isolation. Homey and peaceful. Untouched, save for illegal fishing and mining activities that compromised their beauty.

Oriental Tourist Hub

Puerto Galera, Oriental Mindoro was the opposite. This was one of my earlier destinations, when I first dipped my toe into solo travel. Even then, the beaches within the areas of White Beach and Sabang already felt overdeveloped – it’s even worse now.

I actually had a measure for this “development.” Each visit to Sabang, I made it a point to snorkel in the waters of Small La Laguna, which was a 5 minute walk from Sabang town proper. The area offered impressive snorkeling back in the early 1990s. I would visit and be satisfied with just this activity; island hopping was only an option should I get tired of looking at the same fish.

Each time I came back however, I was less and less impressed. The last time I snorkeled was 4 years ago, and I saw a dying reef. Now, I didn’t even bother.

Each time I came back, there was also a swell in population and structural developments. The shorelines were still recognizable, yes. But my Sabang and White Beach then had become tourism behemoths today, housing countless resorts, tourism workers and tourists.

If you’re looking for muni-muni time alone on a beautiful beach, this would be the wrong place for it. But if you were looking to party in between dives and island hopping, Galera was perfect.

Verde Island Diving

Of course, there was Verde Island, which was just 40 minutes away from the Galera hubs. This trip required a bigger boat and a minimum number of divers so it was offered only by the bigger dive centers during dive season.

As in previous dives in the area, Verde Island wowed me. No, there were none of the big guys – sharks, mantas, whales and such. (I wish!) But what had always impressed me about dives here was the sheer abundance. If ever there was a miting de abanze for fish, this would be the place!

The Tourism Master Plan Difference

I had written about Puerto Galera before. It was one of my first trips for Travel Dive Connect. And, the problems I’d seen and discussed then were the same problems today. In conversations with my European dive guide for Verde, who had been on the island for more than 24 years, we discussed how the conditions grew worse each year.

Proper sanitation and sewage systems were virtually non-existent. Because of clashes amongst barangay and municipality officers, there was now a water problem. Most hillside homes were on sale because water pressure was too weak to reach the area. And, while all this happened, structural work for new resorts seemed to continue, non-stop.

Clearly, Puerto Galera is an uncontrollable tourism giant. And while there is economic gain from all this, there are also costs. Environmental and cultural decline will continue to plague the area as long as stakeholders and government officials pursue unrestrained tourism development.

Compare this to Lubang Island, which took its time even with incentives from the Department of Tourism. They didn’t want the tourism spotlight – not yet – until they were ready.

When they become ready at the end of the year, controls and tourism facilities are in place. There is also a strictly implemented code of conduct for both locals and visitors. Resorts and other tourism businesses operate within guidelines. Travelers, their guides and other service providers follow rules.

So far, the Lubang municipality has proven their resolve to enforce these controls. A dive center had been shut down because their dive staff was caught spear-fishing. A few pasaway mountaineers were caught trekking the Onoda Trail during rainy season, when visitors were forbidden. They were promptly sent back to the municipal office and slapped with fines. Campers are only permitted at specific areas, and only if they get a local guide. Lubang has continually invested in infrastructure, designed to facilitate more comfortable and safe exploration while doing minimal damage/changes to the natural environment.

Driving these is the Tourism Master Plan. And, maybe, here lies the main difference between Oriental and Occidental Mindoro.

It is worth to visit both Oriental and Occidental Mindoro. I have fond memories of these provinces and I know I will come back, time and again. But the differences are stark and hard to ignore.

For now, I trust that what I saw and experienced in Lubang Island and the rest of Occidental Mindoro will be there for me when I long to go back next year, or in five years. With Puerto Galera however, I don’t really know.

I’d like to believe that it’s possible to go back and reverse the effects of an unplanned tourism boom. Perhaps. If not, then I’d like to encourage you to go visit. See both sides and then maybe together we can demand for stakeholders to see tourism not just for the price tag attached to it.

The similarities between Puerto Galera and Boracay are not limited to aesthetics and the sun/sand/sea gratification they offer. The rise of these prime Philippine tourist destinations is practically the same, with Puerto Galera at the heels of Boracay. Both are paradise discovered, developed and overdeveloped, at the cost of the environment and the local communities – what made these places paradisial in the first place.

The similarities between Puerto Galera and Boracay are not limited to aesthetics and the sun/sand/sea gratification they offer. The rise of these prime Philippine tourist destinations is practically the same, with Puerto Galera at the heels of Boracay. Both are paradise discovered, developed and overdeveloped, at the cost of the environment and the local communities – what made these places paradisial in the first place.